In ancient Roman religion, an aedicula (plural aediculae)[a] is a small shrine, and in classical architecture refers to a niche covered by a pediment or entablature supported by a pair of columns and typically framing a statue.[1][2] Aediculae are also represented in art as a form of ornamentation. The word aedicula is the diminutive of the Latin aedes, a temple building or dwelling place.[1] The Latin word has been Anglicised as "aedicule" and as "edicule".[1][2]

Classical aediculae

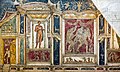

Many aediculae were household shrines (Lararia) that held small altars or statues of the Lares and Di Penates.[3] The Lares were Roman deities protecting the house and the family household gods. The Penates were originally patron gods (really genii) of the storeroom, later becoming household gods guarding the entire house.

Other aediculae were small shrines within larger temples, usually set on a base, surmounted by a pediment and surrounded by columns. In ancient Roman architecture the aedicula has this representative function in the society. They are installed in public buildings like the triumphal arch, city gate, and thermae. The Library of Celsus in Ephesus (2. c. AD) is a good example.

From the 4th century Christianization of the Roman Empire onwards such shrines, or the framework enclosing them, are often called by the Biblical term tabernacle, which becomes extended to any elaborated framework for a niche, window or picture.

Gothic aediculae

As in Classical architecture, in Gothic architecture, too, an aedicula or tabernacle frame is a structural framing device that gives importance to its contents, whether an inscribed plaque, a cult object, a bust or the like, by assuming the tectonic vocabulary of a little building that sets it apart from the wall against which it is placed. A tabernacle frame on a wall serves similar hieratic functions as a free-standing, three-dimensional architectural baldaquin or a ciborium over an altar.

In Late Gothic settings, altarpieces and devotional images were customarily crowned with gables and canopies supported by clustered-column piers, echoing in small the architecture of Gothic churches. Painted aediculae frame figures from sacred history in initial letters of illuminated manuscripts.

Renaissance aediculae

Classicizing architectonic structure and décor all'antica, in the "ancient [Roman] mode", became a fashionable way to frame a painted or bas-relief portrait, or protect an expensive and precious mirror[5] during the High Renaissance; Italian precedents were imitated in France, then in Spain, England and Germany during the later 16th century.[6]

Post-Renaissance classicism

Aedicular door surrounds that are architecturally treated, with pilasters or columns flanking the doorway and an entablature even with a pediment over it came into use with the 16th century. In the neo-Palladian revival in Britain, architectonic aedicular or tabernacle frames, carved and gilded, are favourite schemes for English Palladian mirror frames of the late 1720s through the 1740s, by such designers as William Kent.

Other aediculae

Similar small shrines, called naiskoi, are found in Greek religion, but their use was strictly religious.

Aediculae exist today in Roman cemeteries as a part of funeral architecture.

Presently the most famous aedicule is situated inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in city of Jerusalem.

Contemporary American architect Charles Moore (1925–1993) used the concept of aediculae in his work to create spaces within spaces and to evoke the spiritual significance of the home.

| This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Metasyntactic variable, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. |